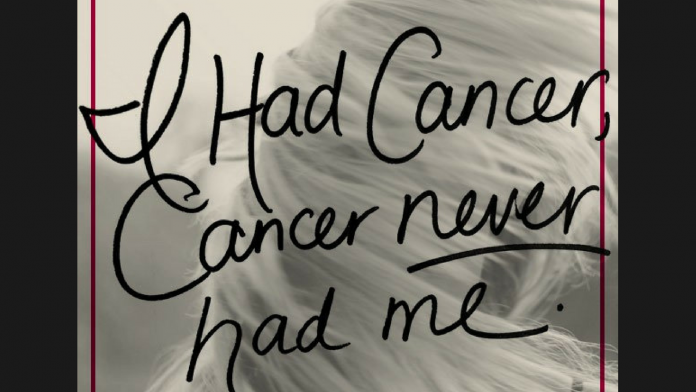

The PTEN Foundation is proud to share a recent article produced by the American Cancer Society featuring our President and Founder, Kristin Anthony. We would like to thank ACS Senior News Editor, Stacy Simon for her assistance in sharing Kristin’s story.

What is PTEN?

PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome (PHTS) is a rare genetic condition that causes an increased risk for certain cancers, benign growths, and neurodevelopmental disorders. PHTS describes any person who is found to have a change, or mutation, in the PTEN gene; some persons may also carry diagnoses of Cowden syndrome or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which are based on their personal medical history and the features they have developed.  One of PTEN’s roles in the body is as a tumor suppressor gene, which means that when it’s working properly, PTEN helps suppress the growth of any cells which are trying to grow out of control and become tumors. All of our genes come in pairs; persons without PHTS have two working PTENgene copies in each of their cells. In people with PHTS one of these PTEN gene copies has a change that makes it notwork in each of the body’s cells. As you can imagine, this puts people with PHTS at increased risk to develop tumors.

Fortunately, most tumors that develop in persons with PHTS are benign, meaning they will not turn into a malignant cancer that can then metastasize or spread, to other body parts. Persons with PHTS commonly develop benign growths, most of which are small, of the skin, tongue, and gums by adulthood. It has recently been discovered that colon polyps of various types, most of which have a low potential to develop into a malignancy, are seen in most adults who have an endoscopy (colonoscopy or upper). Benign breast lumps, thyroid nodules/goiter, and uterine fibroids are also common. Vascular malformations needing surgical intervention may also occur. A benign tumor of the cerebellum called Lhermitte-Duclos disease develops in a minority of adults with PHTS. Macrocephaly (larger than average head size) is common, and some children with PHTS are identified due to the presence of developmental delays and autism spectrum disorders. However, many persons with PHTS had no developmental challenges early in life and have successful careers as doctors, lawyers, or whatever other path they wished to follow.

For a person with PHTS, three different studies have found increased lifetime risks for specific cancer types. The study with the largest number of patients found the following cancer risks (to age 70): breast (85%), thyroid (35%), kidney (34%), uterus (28%), colorectal (9%), and melanoma (6%).  This study also recommends the following cancer screening recommendations:

- Breast (women): start high-risk breast screening (mammogram or MRI) plus clinical breast exam every 6 months starting at age 30

- Thyroid: annual ultrasound starting at age of diagnosis

- Kidney: imaging every two years starting at age 40

- Uterine: see a gynecologic oncologist starting at age 30 to discuss uterine cancer surveillance options

- Colon: baseline colonoscopy at age 35-40; follow-up dependent on number and type of polyps

- Skin: yearly dermatologic checks

Some patients wish to consider prophylactic surgeries, like mastectomy (breast) and hysterectomy (uterus) where at-risk tissue is removed prior to cancer development.

Just like snowflakes, no two individuals with PHTS are alike. While some may develop hundreds of colon polyps, others may only develop a few. Similarly, while some persons have such severe thyroid disease that they require more frequent monitoring or even a thyroidectomy (thyroid removal) surgery, others do not. Given the differing needs of each person, screening and healthcare recommendations often vary from person to person. It can be helpful for persons with a complex condition like PHTS to have a “quarterback†who understands their management needs and helps coordinate visits and screenings with appropriate specialists; for some this quarterback may be their primary care provider, for others it is the genetic counselor or geneticist who made their diagnosis. Persons with PHTS are commonly connected with specialty physicians in the areas of high-risk breast care, endocrinology, gynecology-oncology, dermatology, and gastroenterology to help with their management.

PHTS is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner; this means that each child of an affected person has a 50% chance to inherit their PTENgene mutation and thus also have PHTS. It also means that their siblings, parents, and other relatives are at increased risk to share their specific PTENmutation. Once a PTENmutation is known to exist in a family, it is much cheaper for relatives to have testing for a known mutation as opposed to testing the entire PTENgene. If you have PHTS, consider sharing your PTENtesting results with your relatives. If they have a copy of your test result, they can take it to any genetics provider, who will then be able to discuss testing with them and help them figure out if being tested is the right decision for them at this point in their lives. Genetic counselors in the United States and Canada can be found by going to the National Society of Genetic Counselors website: www.nsgc.org.

For many persons, learning of their or their child’s PHTS diagnosis is a relief and gives them an explanation for many of the medical issues they may have faced during their lives. Some persons may feel scared, angry, or confused about their diagnosis – all of these feelings are valid, and for some people, it’s helpful to share their feelings with others who also have PHTS. Fortunately, there are a few different groups available where patients and families can connect to provide support to one another.

Articles Referenced

- Tan MH, Mester JL, Ngeow J, Rybicki LA, Orloff MS, Eng C: Lifetime Cancer Risks in Individuals with Germline PTEN Mutations. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012, 18(2):400-407.

- Bubien V, Bonnet F, Brouste V, Hoppe S, Barouk-Simonet E, David A, Edery P, Bottani A, Layet V, Caron O et al: High Cumulative Risks of Cancer in Patients with PTEN Hamartoma Tumour Syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics 2013, 50(4):255-263.

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Kets CM, Murphy-Ryan M, Yntema HG, Evans DG, Colas C, Moller P, Hes FJ, Hodgson SV, Olderode-Berends MJ et al: Cancer Risk and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. Familial Cancer 2013.

- Mester J, Eng C: When Overgrowth Bumps Into Cancer: The PTEN-Opathies. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics 2013.

Advice for parents of children with PHTS and autism – Dr. Thomas Frazier

Many children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) have neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism. These children have distinct strengths and challenges in addition to those commonly seen in PHTS without neurodevelopmental issues. In 2016, our team at the Cleveland Clinic Children’s Center for Autism published the first comprehensive description of PHTS with autism.

Many children with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) have neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism. These children have distinct strengths and challenges in addition to those commonly seen in PHTS without neurodevelopmental issues. In 2016, our team at the Cleveland Clinic Children’s Center for Autism published the first comprehensive description of PHTS with autism.

We found that affected children, adolescents, and young adults tend to have significant challenges with mental processing speed and working memory. In other words, they struggle with rapidly processing incoming information and then holding that information in their minds long enough to guide their actions.

Their challenges with working memory and mental processing proved even greater, on average, that what we see in other children on the autism spectrum. Like many people with autism, some individuals with PHTS and autism also have problematic sensitivities to certain sights, sounds and textures and/or difficulty screening out distracting stimuli. At the same time, we did not see overall differences in the severity of core autism symptoms. In other words, their challenges in social communication and repetitive behaviors tended to be like those of other children on the autism spectrum.

We likewise saw a wide range of symptoms and associated challenges, which is also typical of autism. This ranged from mild autism symptoms and average cognitive, or intellectual, abilities to severe autism symptoms with impaired cognition (intellectual disability). These findings reinforce the importance of tailoring interventions and support services for each child, teen, or adult. Along these lines, we developed tailored advice for three distinct groups, as well as general advice for supporting anyone affected by PHTS and autism. As follows:

Group 1: Young children

Young children with PHTS and autism may require early behavioral interventions to optimize daily functioning and learning. Even among children with strong cognitive skills, early intervention can minimize daily challenges such as resistance to change, while broadening interests and promoting social development. For young children with cognitive impairments, early and intensive intervention is particularly important for improving social communication skills. As appropriate, strategies can include the use of a speech-generating device or picture-exchange system and behavioral therapy aimed at decreasing repetitive behaviors and expanding restricted interests as well as step-wise learning of daily living and social skills. In addition, parent training and behavioral and/or medical treatment are crucial when a child is affected by one or more of the health issues that commonly accompany autism. These include disrupted sleep, anxiety, sensory aversions and challenging behaviors. We empower parents when we teach them how to engage with their young children, ease their emotional issues, improve their sleep and replace problematic behaviors with those that increase the quality of life.

Even a short burst of parent training in behavioral strategies can produce lasting benefits for many children and their families.

Group 2: Older children and teens with significant cognitive impairments

The intervention needs of young children often apply to older youth with cognitive impairments. Many older children and teens in this group benefit from an intensive behavioral teaching approach that addresses skills needed for success in school and daily living. It’s important to tailor these social-communication interventions so they make sense to the older child or teen. This includes progressive teaching and reinforcement of social communication strategies that enhance the ability to socialize with others and to ask for what one needs in socially appropriate ways. Such skills go far in improving quality of life for both the child and the family.

Importantly, parents should know that they don’t need to “go it alone.†I encourage them to look for parental support programs in their community, county, and state, in addition to opportunities for financial support and publicly funded therapies for their children. It’s encouraging to see many states and communities increasing the options available to children, adolescents, and adults with autism. So stay connected and continue to inquire.

Group 3: Older children and adolescents with average or above cognitive ability

Social skills tend to rank among the chief challenges when autism affects a child or teen with average or above-average cognitive abilities. Building social skills is an ongoing process that needs to be tailored to each child’s unique – and changing – challenges and strengths. This includes building on personal interests and social motivations. Typically, the most successful interventions combine behavioral and cognitive approaches. The behavioral aspect involves positive feedback to reinforce each step toward mastering an appropriate behavior. Take, for example, the step-wise mastery of acceptable table manners. The cognitive aspect involves learning the “language†of social interactions. This can include learning to maintain an appropriate distance when talking along with the steps to initiating, maintaining and ending conversations. Many cognitively able older children and teens do well in a social skills training and support group.

We’re seeing a growing number of such programs, some covered by health insurance and some included in special education programming. In addition, many individuals with milder impairments do well in a supportive community group such as a church “night out” or after-school club. I encourage parents to seek out more information about local programs. For instance, ask the leaders of a social-skills support group about their training, experience level and the cognitive and/or behavioral approaches they use. Do they base their program on evidence-based strategies (methods that researchers have evaluated and found effective)?

General advice

As a general strategy, keep in mind PHTS-related difficulties with working memory and processing speed. It’s remarkable how effective it can be to simply speak more slowly, especially when giving directions. Of course, you want to personalize this approach to avoid making the child, teen or adult feel “talked down to.” These strategies are likewise important for teachers, therapists, and other caregivers. In particular, I recommend talking with teachers about these working memory and mental processing challenges. Otherwise, the fast pace of instruction in a classroom can prove overwhelming.

The best educational approaches often include presenting information in multiple ways (e.g. with written, spoken and highly visual content) and in a slower, more deliberate fashion. It can also help to repeat information and/or ask questions to check that information is entering working memory.

Capitalizing on strengths

Just as importantly, I urge parents and other caregivers to keep mindful of the strengths that frequently accompany PHTS. One of the most remarkable and common is high social motivation, sincere interest in others and a desire for close contact with loved ones.

We’ve also observed that some children with PHTS and autism show greater cognitive flexibility – or an ability to “go with the flow” – than is typical of others on the autism spectrum. When they do struggle with changes in routine, the associated anxiety and resistance can be milder than is typical with autism.

Looking for and playing to strengths such as these can prove extremely helpful when supporting daily function and learning, and addressing challenging behaviors.

Inspiration for parents

As parents, many of us have felt unprepared to meet the challenges that a neurodevelopmental condition poses for our children. It helps to remind ourselves of the moments that give meaning to our lives, provide us with a sense of purpose and encourage us to be better people.

My colleagues and I are continually inspired by the many families and caregivers who work with us. Their resilience and positive outlook exemplify how challenges can become opportunities. Below is some general advice that can maximize this transformative process.

- Positive reinforcement consistently proves more effective than punishment. It also avoids promoting aggression. Focus on gradually shaping behaviors with positive reinforcement. Your child’s therapist and/or healthcare provider can help you find behavioral training programs for parents of children with developmental disabilities.

- Focus on daily and weekly pleasures. Make sure each week has small, pleasurable experiences, like sharing some popcorn or going on a family walk. Such daily pleasures can enhance happiness and quality of life more than, say, a yearly vacation or even a monthly trip to a favorite place.

- Try to balance accommodating your child’s challenges with addressing or remediating them. In other words, there may be times when it’s more appropriate to make allowances than work on change. This requires a thoughtful approach to deciding when working on a new skill is developmentally appropriate and has real value for your child. Listen to your instincts but also get input from your child’s therapists when deciding how and when to introduce new targets.

- Parenting any child can be draining. Respect that you can and will get tired and frustrated. See if you can trade off with other parents and caregivers. I recommend having mutually understood buzz words like “I need a break” so that you can get prompt relief when needed. If you don’t have other caregivers for mutual support, talk with your child’s therapist, teacher or healthcare provider about available community supports for parents of special-needs children.

- Schedule time for yourself and your important relationships with your spouse, other children and extended family and friends.

- Keep a written record of your child’s new skills, particularly if his or her development feels slow and gradual. It can be a tremendously motivating way to see all the milestones your child has reached over the years. It’s important confirmation that your hard work as a parent is paying off.

I hope this advice and perspective proves helpful. I want all parents of children with neurodevelopmental conditions to realize that this journey can be the most rewarding experience of their lives. Enjoy it and keep up the good work!

– Thomas Frazier, Autism Speaks Chief Science Officer

Dr. Eng’s Journey to PTEN Research

PASSIONATE ABOUT SCIENCE AND MEDICINE FROM AN EARLY AGE

I’ve always wanted to be a doctor, to help people, ever since consciousness. When I was four years old, I knew I wanted to be a scientist. I was inspired by my uncle who became the chair of medicine in Singapore, where I was born, and the prime minister’s physician. Somehow, even at 4, I saw that science drove the evidence for medicine. In the 4th grade, I took a class which included the world’s top medical science discoveries. We were reading about Louis Pasteur, van Leeuwenhoek…

When I was in the 7th grade, my father was sent on a scholarship to do his PhD at the University of Chicago, so we all went, as I am an only child. There, I attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, an inspirational school with inspirational teachers. We had a 10th grade advanced biology teacher whose passion was genetics. He loved it! You could clearly see that. In his spare time, he taught cancer education.

It was then that I said, “I’m going to put cancer and genetics together.” This passion for science and medicine, in the fields of cancer and genetics, led to my current role as the inaugural Chairwoman of the Genomic Medicine Institute and founding Director of its Center for Personalized Genetic Healthcare at Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY PRECISION CARE for PTEN PATIENTS

I have dedicated my career to identifying genes associated with inherited cancers through patient-focused research, with discovery of PTEN germline mutations in Cowden Syndrome patients in 1997. My 20+ year research on PTEN has formed the basis for evidence-based clinical care. As such, I serve as Medical Director of the Cleveland Clinic Cowden/PTEN Multidisciplinary Clinic, the only one of its kind in the world.

We look after patients by gene and the gene pathways, rather than by isolated clinical diagnosis. Irrespective of clinical diagnosis, if a patient has a PTEN mutation, he/she is looked after under our one multidisciplinary roof.

In other words, this is PTEN-informed precision care. Since its inception in 2005, hundreds of patients and families have been referred to our PTEN multidisciplinary clinic from across the globe. We put patients and their families first by ensuring timely patient appointments are coordinated with the appropriate specialists, knowledgeable in PTEN, throughout Cleveland Clinic, including breast specialists, endocrinologists, neurologists, gastroenterologists, psychologists, etc.

PATIENTS PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN RESEARCH DISCOVERIES

Research obtains vital evidence on which the best medicine is practiced. I always wanted to hunt for genes associated with hamartoma syndromes, ever since I was a medical student. I knew then that I had to act to put my high school thoughts of the fields of cancer and genetics together. But, at that time, there were no formal training programs in cancer genetics for both research and clinical care. I therefore sought this unique training at the University of Cambridge, UK, returning to Boston thereafter, to begin my first independent position. My Cowden syndrome patients and families quickly volunteered for my research to look for their gene, and that was PTEN.  Thus, my research goals have been gene-informed diagnosis, prediction of cancer and other clinical risks for accurate genetic counseling, so as to tailor high-risk care, early detection and prevention strategies for the patient and family.

With our first research findings, we were able to give back research-informed clinical care to all the patients who participated in our research and to many others around the world. Realizing that recognition of our patients so they may be referred to expert care was a common issue, we then focused on our patient-research participants to come up with the PTEN Cleveland Clinic Score, a clinical assessment tool that estimates the probability of having a PTEN mutation, after a decade-long study. This score is based on straightforward clinical features which any caregiver can enter, with a resulting score over 10 suggesting referral for expert evaluation.

By prospectively following our group of patient-research participants, we were, for the first time, able to delineate the age-associated and lifetime cancer risks for PHTS, encompassing those of the breast, thyroid, endometrial, colon and skin. We immediately began to reach out to our research participants and patients to inform them of our new findings so that their care would be enhanced. Thus, our model of from the clinic to the laboratory, and back again to clinical practice, has been successful and we will continue this effective strategy.

As such, PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome (PHTS) patients and families just like you have inspired and facilitated these research discoveries because of their decision to participate in research.

Current ongoing studies include:

- research about patients with PTEN mutations with and without ASD, which combines clinical patient information with DNA, RNA and protein studies of PTEN and related pathways to better understand molecular, brain and behavioral differences and their development;

- parallel study asking what is the switch that dictates how/why a PHTS individual has ASD, cancers or both;

- our 20-year strong PHTS study on cancer risk;

- an examination of the gut and oral microbiome (bacteria) in patients with PTEN mutations to determine whether there is an association with outcomes, specifically as cancer and ASD; and

- a pilot clinical trial of everolimus for individuals with PTEN-ASD.

TOWARD BETTER MEDICAL CARE

Our ability to care for and study PHTS patients helps us to move toward better medical care.

For this reason, I am excited to be working with the PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome Foundation to plan a first-of-its-kind, international, patient-centered meeting on March 25-26, 2018, in Hunstville, Alabama. I, along with several of my colleagues, will be speaking on topics ranging from PHTS cancer risks and clinical screening recommendations, daily management of autism and developmental delays, and current research studies for PHTS patients. As a patient-focused meeting, it will be a tremendous opportunity for you to not only learn more but also to connect with others with PHTS. I hope to see you there!

By:  Charis Eng, MD, PhD, FACP, Cleveland Clinic

You don’t know what’s in you – until they, the surgeons, go in you.

You don’t know what’s in you – until they, the surgeons, go in you.